Don't call me Luddite!

- stasimos

- 28 mag 2018

- Tempo di lettura: 7 min

Aggiornamento: 29 mag 2018

#technologicalunemployment #technology #lavoro #trasformazione #unemployment #automation #artificialintelligence #industrialrevolution #economics #innovation #labour #disoccupazionetecnologica #disoccupazione #jobpolarization #inequality #gigeconomy

“From the sixteenth century, with a cumulative crescendo after the eighteenth, the great age of science and technical inventions began […] The growth of capital has been on a scale which is far beyond a hundredfold of what any previous age had known. And from now on we need not expect so great an increase of population […] At the same time technical improvements in manufacture and transport have been proceeding at a greater rate in the last ten years than ever before in history […] In quite a few years our lifetimes I mean-we may be able to perform all the operations of agriculture, mining, and manufacture with a quarter of the human effort to which we have been accustomed. For the moment the very rapidity of this changes is hurting us and bringing difficult problems to solve […] We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come, namely, technological unemployment […] But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem. I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is today. There would be nothing surprising in this even in the light of our present knowledge. It would not be foolish to contemplate the possibility of a far greater progress still […] Our relative needs, those which satisfy the desire of superiority, might be insatiable, but as soon as the absolute needs will get satisfied we will have time to devote our energies to non-economic purposes […] I draw the conclusion that, assuming no important wars and no important increase in population, the economic problem may be solved, or be at least within sight of solution, within hundred years. This means that the economic problem is not-if we look in the future-the permanent problem of the human race.[…] Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem, how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well […] For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavor to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!”

(Keynes, On possibilities of our Grandchildren, 1930. evidence stands for my paraphrase )

In the political pamphlet above, Keynes, with the aim to reassure people during the “dark hours” of the Great Depression, depicted a future for one hundred years to come that, on the wave of technological improvement, would have been characterized by a greater degree of freedom from economic constraints. Having to work less hours, people would have get able to spend their time to fulfill non-economic interest. The increased productivity of machines would have lead, rather than to the substitution of labor, to shorter work shifts. Nevertheless, twelve years before the “deadline” Keynes forecasted, his far too optimistic visions seems even farer to reach than it was at his time.

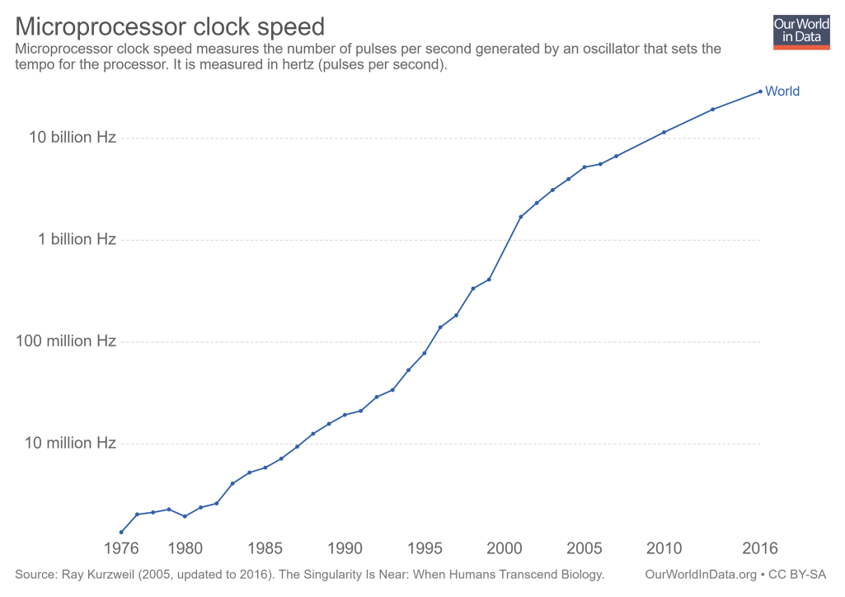

Nowadays, a new technological revolution seems at hand due to: an increasing computational power at decreasing cost, rapidly growing datasets and advances in machine learning algorithms. As a result, the increased ability of Artificial Intelligence to solve more and more complex problems is threatening to significantly, if not completely, substitute human work. This result might be far too pessimistic and recalling a dystopic view. Ever since the first industrial revolution, in fact, any period of technological change has increased the fear of technological unemployment. Nevertheless, despite some short-term frictions, so far the economy has demonstrated to be able to gradually cover the job lost mainly by: complementarity in job opportunities, increase in productivity and the emergence of new sectors.

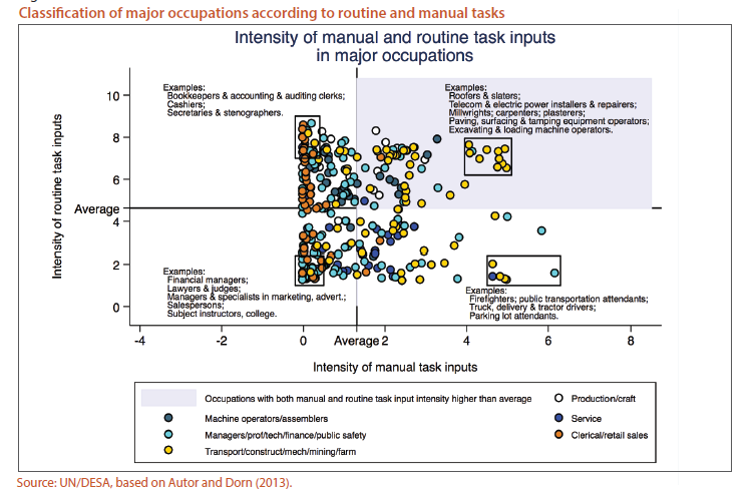

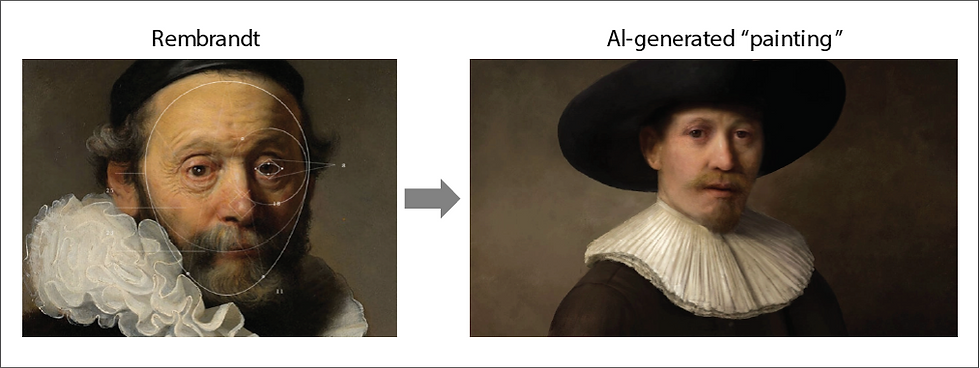

Despite the historical evidence, the nature and fast pace (Figure.3,1.4) of today’s technological change stems for an higher risk of permanent technological unemployment. Not only machines are becoming increasingly able to substitute, other than routine jobs, also cognitive ones (Figure 2, 3, 4); but ,most of all, it seems more and more hard to either create new jobs or to win the so-called education race (i.e. catching up the technological change before the emergence of a further wave of new technologies).

As a consequence, those effects generated by technological change that have historically been temporary might extend to the long-run . This seems much more likely if a blind faith in the market capabilities to automatically restore the equilibrium won’t induce some policy interventions.

The risks are hence high and mainly related to: Job polarization, Income inequality and rise of contingent work.

- JOB POLARIZATION: The combination of routine-based technological change and offshoring has led to the substitution of most of the middle occupations, namely those involving either cognitive or manual routine skills (Figure 5 and 6)

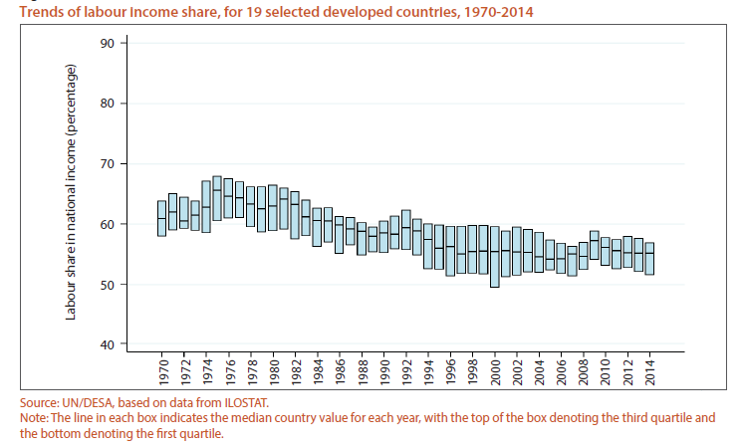

- INCOME INEQUALITY: The hollowing out of the middle of the wage distribution, due to the job polarization, tend to increase the income inequality. In fact, only high and low skilled occupations, involving respectively non-routine cognitive and manual skills, will survive (Figure 7). While being an important determinant, labour income inequality cannot fully account for the evolution of income inequality over the years. Income inequality is also influenced by the distribution of income between labour and capital, which again is affected by technological changes. We can observe a broadly declining labour share in national income in many developed countries since the mid-1970s, and in some developing countries since the 1990s. As labour income accounts for a larger share of income for households at the bottom of the distribution than for those at the top, and capital is typically more unevenly distributed across capital owners, a fall in the labour share in national income is associated with a worsening income distribution (Figure 8)

- RISE OF CONTINGENT WORK: (e.g Gig economy: Food delivery platforms, Transport Platforms, Accommodation Platforms) The current technological changes also contribute to a shift away from traditional work arrangements to “contingent work”. This has dangerous consequences both on labour protection and human conditions (Figure 9).

On the first hand, workers in the gig-economy are classified as independent contractors (Risak and Warter, 2015; Smith and Leberstein, 2015; Sprague, forthcoming). This allows shedding not only potential vicarious liabilities and insurance obligations towards customers but also a vast series of duties connected to employment laws and labour protections, including – depending on the relevant jurisdiction – compliance with minimum wage laws, social security contribution, anti-discrimination regulation, sick pay and holidays.

On the second hand, workers become considered as software extension and are meant to run equally smoothly otherwise they got a bad review and get fired or have less chance to work (no possibility to book shifts). The technology-enabled possibility of receiving instant feedbacks and rates of workers’ performance is pivotal in ensuring businesses both flexibility and control at the same time (Sachs, 2015a). First of all, it reduces the need of internal performance-review personnel and mechanisms, contributing to keeping organisations lean.

It also allows “shifting” or outsourcing a good deal of customer care to individual workers.

It is difficult to estimate the number of workers in the gig-economy. Businesses are sometimes reluctant to disclose these data and, even when figures are available, it is hard to draw a reliable estimate, since workers may be registered and work with several companies in the same month, week or even day (Singer, 2014). Data collected and elaborated by Smith and Leberstein (2015) for the principal platforms and apps, however, show that this is clearly a non-negligible phenomenon (Figure 10)

How the new wave of technologies will shape labour markets and income distribution, depends on the institutions and policies that are in place at the national and global level. Governments need to take into account that they operate with significant uncertainty, and this would support a trial-and-error approach that can be adapted according to new experiences and developments.

Last but not least our relationship with technology has a great importance. Any attempt to uniquely interpret the emergence of technique either as a mean of dominance or of liberation seems missing the point. Many question are more relevant: what do we know about technology? What are the consequences it implies? How it change us and the surrounding world? What are its functions and the different ways it can be used? How do we make its use beneficial to the whole society?

“E poi ci sono tutti i miti tecnologici, positivi e negativi, che troviamo nelle forme

più raffinate presso gli intellettuali borghesi e riformisti: quelli più positivi sono facili a

svelarsi; sono quelli che dicono che il socialismo verrà sull'onda dell’automazione, per cui

questo futuro mostruoso che sarebbe un mondo automatizzato nel capitalismo, questa che

è soltanto un’idea limite, evidentemente, viene rovesciata in forma positiva come

liberazione dell’uomo, con tutte le conseguenze. Ma quelle più interessanti sono le

ideologie tecnologiche negative, cioè tutte quelle ideologie che tendono ad affermare che

sì, il processo dell’industria riduce l’uomo a una completa alienazione nel momento

produttivo; e tuttavia questo è il prodotto dell’industria, non è il risultato del capitalismo,

dello sviluppo capitalistico, è l’industria in sé che è fatta così. E allora l’uomo come si può

liberare? Niente, dentro l’industria non si libera, non c’è niente da fare; però lo possiamo

liberare fuori, gli possiamo dare il tempo libero, sempre di più: gli possiamo dare gli asili

ecc. E non solo l’automobile: anzi, per solito, questi ideologi ripudiano queste cose volgari

ancora legate al mondo della produzione. Gli dobbiamo dare i campi, il ritorno alla

natura… La mattina vai in fabbrica, però il pomeriggio , la sera, quest’uomo deve

riprendere contatto con la natura, con le forze naturali e via dicendo”.

(Panzieri R., Sull'uso capitalistico delle macchine nel neo capitalismo, in Lotte operaie nello sviluppo capitalistico, Einaudi 1976, p.44)

1 commento